April 10, 2024 6 min read

Seven Key Health Hazards in Construction

Industry:

Solution:

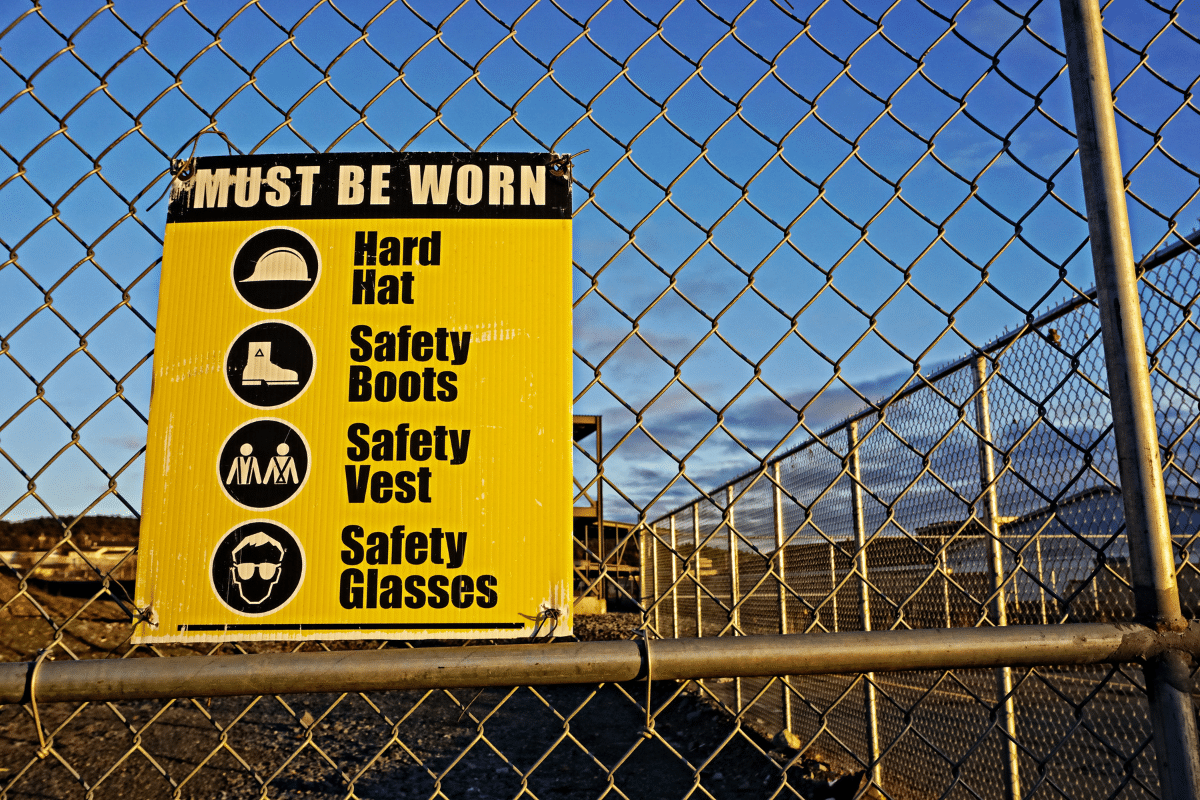

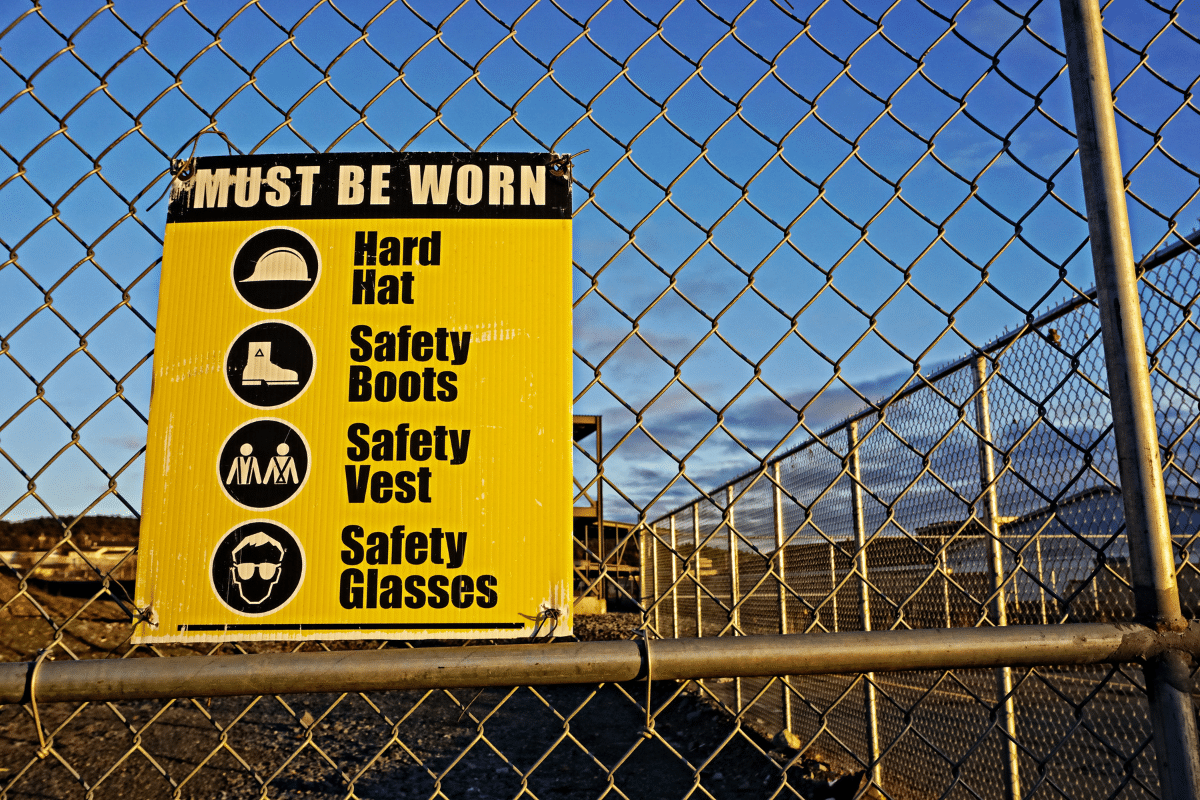

In the construction industry, prioritizing health hazards is crucial for ensuring the well-being of workers. Certain hazards pose more immediate and severe risks than others, requiring prioritized attention and mitigation efforts. In this article, we’ll explore the most urgent health hazards in construction and discuss strategies to mitigate them effectively.

Seven Health Hazards in Construction to Beware of and Guard Against

Construction work encompasses various health risks that workers, and employers, need to be aware of and protect against. We’ve chosen the seven most important hazards to focus on because they’re common in construction, can lead to severe injuries or worse, and need urgent attention to reduce risks.

- Falls

- Electrical Hazards

- Confined Spaces

- High Temperatures

- Manual Material Handling

- Noise

- Air Contaminants

Construction Safety Training Guide

This comprehensive guide covers construction safety hazards, OSHA's construction training requirements, developing an effective safety training program, and help with your construction safety training efforts

Download Guide

1. Falls

Falls are the leading cause of fatalities in the construction industry, making them the most urgent hazard to address. Workers are at risk of falls from heights due to unprotected edges, unsecured ladders, and unstable scaffolding. Employers should prioritize fall prevention measures such as guardrails, safety nets, and personal fall arrest systems (PFAS) to protect workers from fall hazards.

Resources for Fall Prevention:

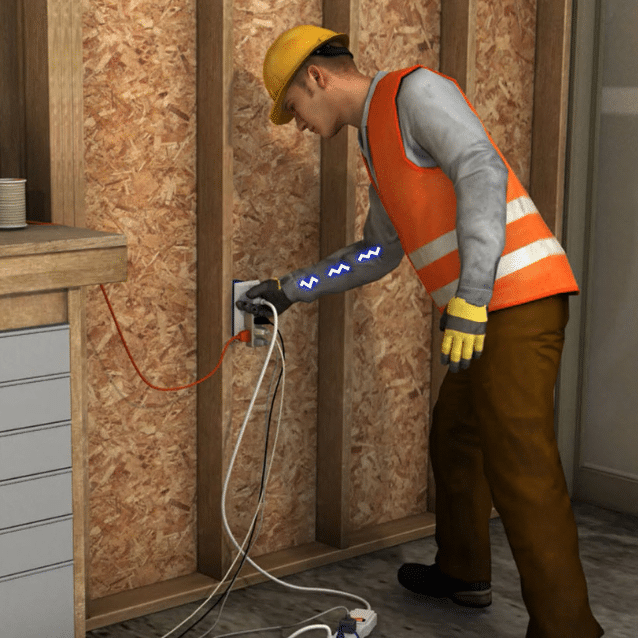

2. Electrical Hazards

Electrical hazards pose significant risks of shocks and electrocution on construction sites. Exposure to live wires, improper use of electrical equipment, and inadequate grounding can result in severe injuries or fatalities.

Employers should prioritize electrical safety measures, including proper training, use of ground-fault circuit interrupters (GFCIs), and regular inspections of electrical systems.

Resources for Electrical Safety:

3. Confined Spaces

Confined spaces present risks of asphyxiation, engulfment, and toxic exposure to construction workers. Entrapment in confined spaces like tanks, tunnels, and pits can lead to fatal accidents if proper precautions are not taken.

Employers must prioritize confined space safety by conducting thorough risk assessments, implementing entry procedures, and providing adequate training and personal protective equipment (PPE) to workers.

Resources for Confined Space Safety:

4. High Temperatures

Working in hot environments exposes construction workers to heat-related illnesses such as heat exhaustion and heat stroke. As temperatures rise, the risk of heat-related hazards increases, making heat stress prevention crucial. Employers should prioritize measures such as providing shade, hydration stations, and frequent rest breaks to protect workers from heat-related illnesses.

Resources for High Temperatures:

5. Manual Material Handling

Manual material handling involves lifting, carrying, and moving heavy objects, which can lead to musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) among construction workers. While not as immediately life-threatening as falls or electrical hazards, MSDs can result in chronic pain and disability if left unaddressed.

Employers should prioritize ergonomic training, mechanical aids, and task redesign to minimize the risk of MSDs.

Resources for Manual Material Handling:

6. Noise

Construction sites often generate high levels of noise, posing risks of hearing loss and other health issues. While not as overtly dangerous as falls or electrical hazards, long-term exposure to loud noise can have serious health consequences. Employers should prioritize noise control measures to protect workers’ hearing health.

Resources for Noise Control:

7. Air Contaminants

Air contaminants, such as dust, fumes, and gases, can result from various construction activities, posing risks to respiratory health. While not always immediately noticeable, exposure to airborne contaminants can lead to chronic respiratory problems and other health issues over time.

Employers should prioritize measures to control exposure to air contaminants, including ventilation systems, respiratory protective equipment, and proper handling of hazardous materials.

Resources for Air Contaminants:

Don’t Ignore Health Hazards in Construction

By understanding and addressing these key health hazards in construction, employers and employees can create safer work environments. Refer to the provided resources and take proactive measures to protect construction workers from manual material handling, noise, air contaminants, and high temperatures on the job site.

EHS Management for Architecture, Engineering, and Construction

Easily report and investigate safety incidents, track data, and complete OSHA logs to keep employees and contractors safe

Learn More

Why Choose Vector Solutions for Construction Safety?

Vector Solutions offers tailored safety training and management solutions designed to meet the unique needs of the construction industry, addressing critical health hazards in construction.

With deep knowledge and experience, we understand the specific safety challenges facing the construction sector. We use that knowledge to create award-winning eLearning courses to fill skills gaps, increase safety, and help improve employee retention.

“[Vector Solutions] gives us the ability to create consistent training experiences for our employees and the ability to deliver those effectively every time—that’s priceless.”

— Training Analyst

If you want to see any of our solutions in action, request a demo today.